A Question about Tachyons

Table of Contents

- Preliminaries on the Klein-Gordon equation

- Phase and group velocities

- Characteristic fields and speeds

- Causality in quantum field theory

- Further reading

Preliminaries on the Klein-Gordon equation

Suppose there is a scalar field w(x) (where x is shorthand for the spacetime coordinates t,x,y,z) with potential

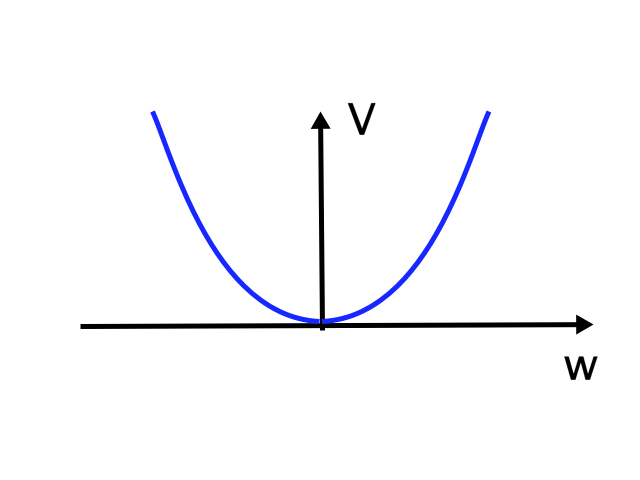

\[V(w) = \frac{1}{2} M w^2\]If M is positive, then the potential looks like this:

Clearly, this potential will tend to push the field toward a value of zero if it is not already zero. The state w(x)=0 is called “the vacuum” because this is the minimum of the potential. Note that when physicists refer to “the vacuum”, we don’t mean “nothing”. The field is still there; it just has value zero. If the potential were

\[V(w) = \frac{1}{2} M(w-1)^2\]then the vacuum would be at w=1.

Anyway, when M>0 we usually write it like this

\[M = m^2\]and say that the field w has mass m.

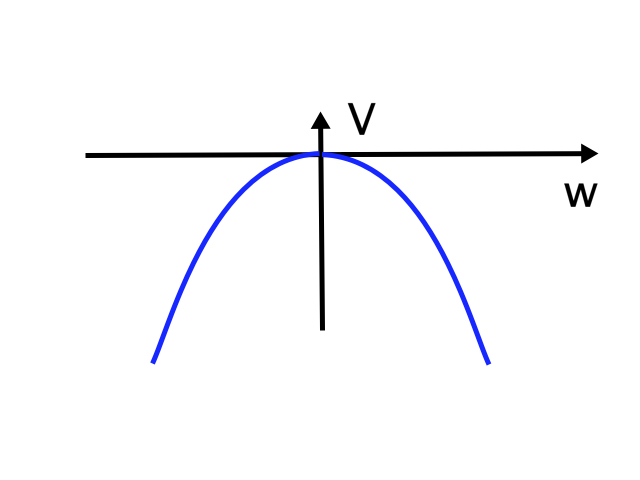

But suppose M<0. Then the potential looks like this:

Your intuition tells you that the equilibrium w=0 is unstable. If the field is a little bit positive, it can release energy by getting bigger. If it’s a little bit negative, it can release energy by getting more negative. Such a field is called a tachyon field.

You will sometimes encounter claims (not only in the popular press, but in published journal articles) that tachyon fields correspond to particles that travel faster than light or fields that send signals faster than light. This should strike you as odd. How could putting an otherwise special relativity-compliant field near an unstable equilibrium cause it to start exhibiting superluminal motion? It can’t, but it is instructive to see how even smart, knowledgable people sometimes get this impression. It will help you get a clearer understanding of what the various speeds in classical field theory really mean. (Toward the end, I will say something about causality in quantum field theory as well, but this essay will mostly be classical.)

Before really diving in, let’s get the equation of motion for this field. We shall work throughout in units for which the speed of light c=1. We shall also assume a Minkowski metric, that is that we are working in flat spacetime in Cartesian coordinates. The action is

\[S[s] = \int d^4x \left[-\frac{1}{2}\eta^{\mu\nu}\partial_{\mu}s\partial_{\nu}s - M s^2\right]\]Recall S is a functional: it takes a 4D function as input and spits out a number. The classical equation of motion is a stationary point of the action. That is, a classically allowed spacetime history w( x ) is one with the property that if you slightly alter s( x ) in any arbitrary way, the action will not change to linear order in the perturbation:

\[S[w(\mathbf{x} + \delta w(\mathbf{x})] - S[w(\mathbf{x})] = 0 + O(\delta w^2)\]Taking the variation of the action and integrating by parts at the usual occasion, one gets the Klein-Gordon equation

\[\eta^{\mu\nu}\partial_{\mu}\partial_{\nu}w - M w = 0\]Everything is easier to see in one spatial dimension, and no essential is lost, so let us restrict ourselves to one spatial dimension x:

\[\left[-\frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2} + \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} - M\right]w = 0\]By the way, let’s now check our intuition about stability. Consider the limit where w changes in time but does not vary in space. (Think of w(x) as a horizontal line that can move up or down in time but stays horizontal.) Then we would have the ODE

\[\frac{d^2 w}{dt^2} = -M w\]You will immediately recognize that if M>0, the solutions will be simple harmonic motion (sinusoidal)–what we expect for a perturbed stable equilibrium. If M<0, the solutions are growing or decaying exponentials–what we expect for a perturbed unstable equilibrium.

Phase and group velocities

Let us guess (correctly) that there are wavelike, complex exponential solutions.

\[w = e^{ikx - \omega t}\]Plugging this into the Klein-Gordon equation, we get the dispersion relation:

\[\omega^2 = k^2 + M\]For positive M, the frequencies will be real for any wavenumber. (Again, positive M is stable.) For the tachyonic case of M<0, it turns out there are some stable oscillations but only if the wavenumber is high enough (i.e. the wavelength short enough) such that

\[k^2 + M > 0\](Hereafter I will only consider positive frequencies.)

The phase velocity is

\[v_p \equiv \frac{\omega}{k} = \frac{\sqrt{k^2 + M}}{k}\]This is greater than 1 for the real mass (positive M) case and less than 1 for the tachyonic (negative M) case. Recall that c=1 in our units. Does this mean real mass spinless particles travel faster than light, while tachyons travel slower than light? That’s certainly not what we were expecting to find! It’s also not true.

What does phase velocity actually mean? From its definition above we can rewrite the plane wave solution as

\[w = e^{ik(x-v_p t)}\]So we see that the phase of the wave at position x at t=0 will be the same as the phase of the wave at location

\[v_p t\]at time t. The sinusoid moves to the right at the phase velocity. However, just because these two events will have the same phase of a scalar field doesn’t necessarily mean that the wave phase at the earlier event caused the wave phase at the later one. In fact, since for positive M the two events will be spacelike separated, we know that there is no influence whatsoever between the two events. Indeed, different frames will disagree about which came first or whether they are simultaneous.

The question is whether what happens to the field at one event can influence what happens at another spacelike separated one. That’s what superluminal travel really means.

You are probably remembering now that the more physically meaningful quantity is the group velocity, which is

\[v_g \equiv \frac{d\omega}{dk} = \frac{k}{\sqrt{k^2 + M}}\]For positive M, this will be less than one (subluminal). For negative M, it will be greater than one (superluminal). Here, then, is what we were expecting: real mass scalar fields propagating subliminally, tachyonic fields propagating superluminally.

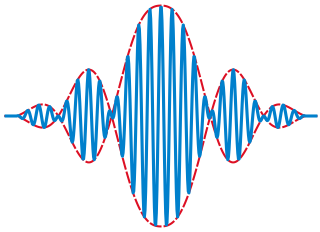

But hold on; we’d better ask ourselves what group velocity really means. Group velocity has to do with when we have a combination of waves of different k which make up a wave packet. Here is a picture of a wave packet from Wikimedia Commons:

The red dotted curve is the envelope. The group velocity formula above gives, under certain conditions, the speed at which the envelope of the wave packet moves. We are, then, still dealing with the motion of a pattern across spacetime. The peak of the envelope at one time is not necessarily caused by its peak at an earlier time; it might be just what shifts in constructive and destructive interferance happen to do to the wave pattern.

In fact, there are particular issues with using the group velocity for tachyonic Klein-Gordon waves. The Klein-Gordon dispersion relationship is nonlinear, which means group velocity is a function of k, which means the envelope doesn’t just move; it changes shape as it moves. So the packet won’t just move at this speed we calculated. Futhermore, for the tachyonic case, the low-k modes, remember, are exponential rather than wavelike, so if these are present the relationship between group velocity and envelope speed doesn’t apply. If we demand that low-k modes are absent, then we are restricted on what sort of packets, what sort of fields, we are allowed to have. Restrictions on the shape of w at a moment in time means that the field values at these spacelike separated events are not really independent for a reason other than causal influence.

Characteristic fields and speeds

Let us then look at where causal influence really comes into our theory, in the characteristic structure of the equation of motion. Rather than review how this is done for a general PDE, let’s start by factoring the Klein-Gordon equation

\[\left[\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial x} - \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \right)\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \right) - M\right]w = 0\]Defining new variables

\[u \equiv \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right) w \qquad v \equiv \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right) w\]The fields w, u, and v obey first-order PDEs

\[\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right) u = -Mw\] \[\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right) v = -M w\] \[\frac{\partial w}{\partial t} = \frac{1}{2}\left(u+v\right)\]Now, the first order operator

\[\frac{d}{dt} \equiv \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \right)\]is just an advection operator. If M=0, it would mean that u just shifts to the right with speed 1. We can think of the characteristic field u as part of the information in the field that flows to the right at the speed of light. The mass term M w doesn’t have any derivatives and so doesn’t connect neighboring points. It doesn’t affect the information flow. One can, in fact, think of the above as an ODE rather than a PDE.

\[\frac{du}{dt} = -M w\]Here du/dt means the rate of change of u with respect to t as one moves along a right-going null path.

Similarly, the characteristic field v flows to the left at the speed of light. These spacetime paths of information flow, i.e. the characteristics of the PDE, show information traveling along light cones. The lack of spatial derivatives in the remaining equation for w gives another characteristic speed of zero, indicating that information flows inside light cones and not just on them. There is no information that flows faster than 1, though, regardless of the sign of M.

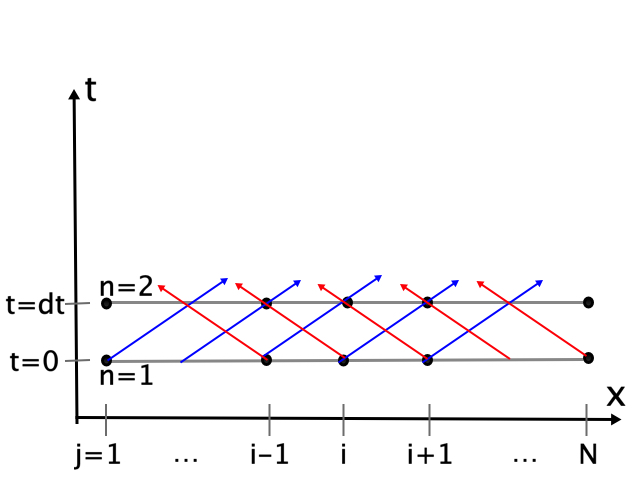

To make this clearer, let’s imagine using characteristics to solve the Klein-Gordon equation numerically. Suppose we introduce a 1D grid with N points with constant spacing dx between points. Computers don’t have infinite memory, so we will only keep track of functions at the gridpoints. Each gridpoint shall be labeled by an index j running from 1 to N. Say at time t=0, we know w, u, and v at each grid point. We will also discretize in time, i.e. calculating functions only at a finite sequence of moments, and we assign an index n to each moment, with n=1 at t=0. The time from one of these moment to the next is called the timestep dt, and I choose dt=dx so that characteristics connect grid points at on time to grid points at the next time. The setup looks like this:

Knowing everything at n=1, I want to calculate everything at n=2. Here’s a way I might do this. Consider a point j=i somewhere in the middle of the grid. First I will take into account the information flow. u information flows rightward (on blue lines), so ignoring mass, we would have u(j=i,n=2)=u(j=i-1,n=1). We take mass into account by thinking of u as evolving according to an ODE along blue lines, and we’ll approximate this ODE using a simple first-order, Eulerian finite differencing (I didn’t say this is the best way to numerically integrate these equations), I would have instead

\[u(j=i,n=2)=u(j=i-1,n=1) - M w(j=i-1,n=1)dt\]Similarly, v information flows along left-going (red) null lines.

\[v(j=i,n=2)=v(j=i+1,n=1) - M w(j=i+1,n=1)dt\]Finally, red and blue information combine to give w

\[w(j=i,n=2) = \frac{1}{2}\left[u(j=i,n=1)+v(j=i,n=1)\right]dt\] \[w(j=i,n=3) = \frac{1}{2}\left[u(j=i,n=2)+v(j=i,n=2)\right]dt\]To evolve endpoints, we must specify boundary conditions. The characteristic formulation tells us exactly what information to provide at boundaries (and what not to provide) to have a well-posed problem. This is why, even though real numerical integrations of PDEs don’t usually use the above method, calculation of the characteristic fields and their speeds is at the heart of designing boundary conditions. Clearly, from the picture, u information flows into the grid from the left, and v information flows in from the right. Therefore, for all n>1, we must specify (somehow or other) u on j=1 and specify v on j=N. We should not provide anything else.

Causality in quantum field theory

In classical field theory, w(x,t) is a function. It takes some numerical value at each x and t, and the values of these numbers tell us which of all possible worlds we are living in. In quantum field theory, there is a field operator w(x,t) which obeys the Klein-Gordon equation but which plays a very different role than in the classical theory. In particular w is the same no matter what the state of the world is. The information about which of all possible worlds we are actually in is carried by the state, represented (for a pure state) by a vector in Hilbert space. The operator w(x,t) acting on the state roughly has the effect of changing the state by adding a particle/field excitation at the event (x,t). Compare this to the more familiar case of particles. In Newtonian mechanics, the momentum p of the particle is a number. The number will be different depending on how fast the particle is moving. In quantum mechanics p is an operator, the same regardless of the particle’s motion. Information about the latter is contained in the state vector (the wavefunction, if you prefer). If the state is an eigenvector of p, then the value of the particle’s momentum (i.e. what it would certainly be found if measured) is the eigenvalue. p in the Hamiltonian is responsible for altering the state so that packets of probability move in space. The situation is analogous in field theory.

Recall that if two operators do not commute, they are not simultaneously specifiable: the state cannot have definite values of both, so you can’t prepare a system in definite states of both, and you can’t measure one without changing the state so it doesn’t have a definite value of the other. The two operators are in this sense not independent.

This property is used to establish lack of causal influence in quantum field theory. If two points are spacelike separated and there is no superluminal information flow, then the field at one point should be independent of the field at the other. Their operators, then, should commute.

\[[\mathbf{w}(x,t), \mathbf{w}(x',t')] = 0 \qquad {\rm if } |x'-x| > |t'-t|\]To build a second quantized theory of this field, we should construct this operator w(x,t), e.g. by writing the field as a Fourier sum of modes and then replacing the mode coefficients with creation and annihilation operators. Then we can study the field operator’s commutator.

For tachyons, there are technical issues that arise, having to do with the fact that the modes are exponential (imaginary frequency) for small k. What many, beginning with Feinberg (1967), have done is to simply set a lower limit on k, excluding all modes that would have imaginary frequencies. One then artificially has a stable vacuum with plane wave modes that look like regular particle excitations. However, one then finds that the tachyon field at any particular time is restricted in its spatial dependence: one can’t just lay down any initial data one wants at t=0, as one would expect one could. If one does this, then one can show that the resulting field commutator is nonzero even for spacelike separated points. As I have argued above, this is probably an artefact of having restricted the allowed modes; these restrictions mean that the field at separated points on a spacelike hypersurface will not be independent. It doesn’t make sense that one can enable a field to propagae information superluminally just by sitting it at the top of an unstable equilibrium.

Further reading

Here are some papers, not all of which I agree with, but all of which I think are valuable. One way of tackling this issue that I didn’t talk about is constructing the retarded Green function and seeing if it has support outside of the light cone. The answer is that one can construct a causal retarded Green function (which is what one needs for the demonstration), but it is also possible, even for real mass theories, to build Green functions that appear to involve superluminal communication, so one must be careful in interpretting this. This issue is dealt with in detail in the final paper below.

-

Possibility of Faster-Than-Light Particles by G. Feinberg, Phys. Rev. 159, 1089 (1967)

-

Suyerluminal Behavior, Causality, aud Instability by Y. Aharonov, A. Komar, and L. Susskind, Phys. Rev. 182, 1400 (1969)

-

Do tachyons travel more slowly than light? by L. Robinett, Phys. Rev. D 18, 3610, (1978)