A Thought Experiment on Black Holes

You will have heard the following about black hole event horizons. 1) The horizon is a surface of no escape. No information can travel from inside the horizon to outside the horizon. 2) There is nothing locally special at the horizon location. It’s empty space. An observer generally can’t know when it reaches it. If the black hole is massive enough, tidal forces near the horizon might not be strong, so a person might cross comfortably into the black hole.

Thus the question. Suppose I am near a black hole’s event horizon, the black hole having sufficient mass that tidal forces at my location are negligible. To maintain my bodily integrity, we shall also assume that parts of my body are at rest with respect to each other. (Although well-defined global inertial frames do not exist in general relativity, they do exist locally, so over the length of my body we can make sense of the various parts having zero relative velocity.) Let us say my left hand is inside the horizon, while my head is outside the horizon. Can I see or feel my hand? Because if not, that wuold be pretty noticeable, right?

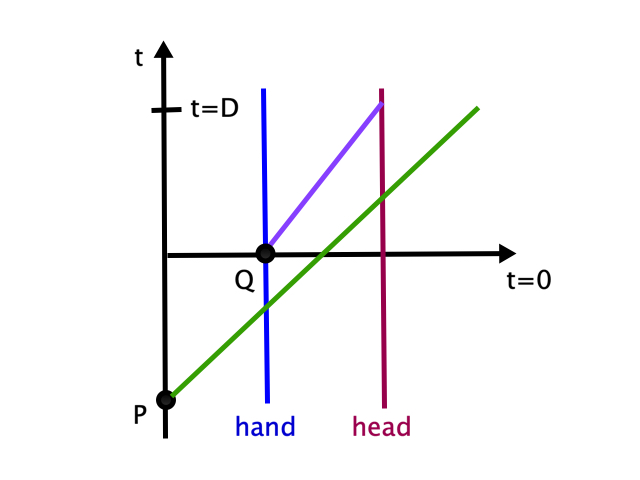

First, let’s solve an analogous problem in flat spacetime. A future light cone is also a “surface of no escape”: timelike worldlines can enter but not leave, and information cannot get out of it. It is always the case that, at a given moment–call it \(t=0\), my left hand is in the future light cone of some past event P while my head is outside. Meanwhile, I can feel my hand because sensory nerve signals are constantly traveling at rather less than the speed of light from my hand to my brain. Since my hand and head are at rest with respect to each other, we can work in their common frame. Let’s draw all this in a spacetime diagram:

From the diagram, it is clear that there is no paradox. Events inside the light cone cannot have information from events outside. This requires that my hand at \(t=0\) can’t influence my brain at \(t=0\), but we knew that anyway, because those events are spacelike separated. My hand at \(t=0\) (event Q) sends a signal to my brain, and by the time it reaches my head (at \(t=D\)), my head is inside the light cone. At \(t=0\), my brain is receiving a signal from my hand at \(t=-D\); here both the hand-sending event and the brain-recieving event are outside the light cone, so again, no problem. At no point does my hand go numb (or invisible).

Now let’s go to the black hole case. The spacetime metric of a stationary, nonspinning black hole is given by the Schwarzschild line element:

\[ds^s = -\left(1 - \frac{r_s}{r}\right)dt^2 + \left(1-\frac{r_s}{r}\right)dr^2 + r^2 (d\theta^2 + \sin^2\theta d\phi^2)\]The event horizon is at \(r=r_s\), where \(g_{tt}=0\) and \(g_{rr}=\infty\). The infinity would lead one to think that this radius is a singularity, but in fact it’s just a sign that the coordinate system has gone bad. Coordinate singularities are apt to trick us about their locations–consider how, on a latitude-longitude map, the North and South poles look like lines rather than points. (The polar coordinate system is singular there, and the proper distance along these “lines” is zero.) Similarly, in this coordinate system, \(r=r_s\) looks like a fixed location, and we are used to fixed spatial locations marking out timelike paths in spacetime (i.e. it’s usually possible for there to be an observer sitting at a fixed location), but in this case, this appearance is deceiving.

In 1932, Georges (“father of the big bang”) Lemaitre produced a demonstration that the freezing-at-the-horizon effect is in fact just a coordinate artifact. He introduced new coordinates \(T\) and \(X\) in which the behavior at the horizon is regular. Set

\[dT = dt + \sqrt{\frac{r_s}{r}}\left(1 - \frac{r_s}{r}\right)^{-1}dr\] \[dX = dt + \sqrt{\frac{r}{r_s}}\left(1 - \frac{r_s}{r}\right)^{-1}dr\] \[r = \left[\frac{3}{2}(X-T)\right]^{2/3}r_s^{1/3}\]It’s a nice little exercise for you to show that, in these coordinates, the line element is

\[ds^2 = -dT^2 + \frac{r_s}{r} dX^2 + r^2 (d\theta^2 + \sin^2\theta d\phi^2)\]Note that, very near the horizon, the spacetime now looks nearly Minkowski. For the rest of this problem, let’s zoom in on a region close to the horizon. We’ll set \(r_s/r\approx 1\) and consider only radial movements \(d\theta=d\phi=0\).

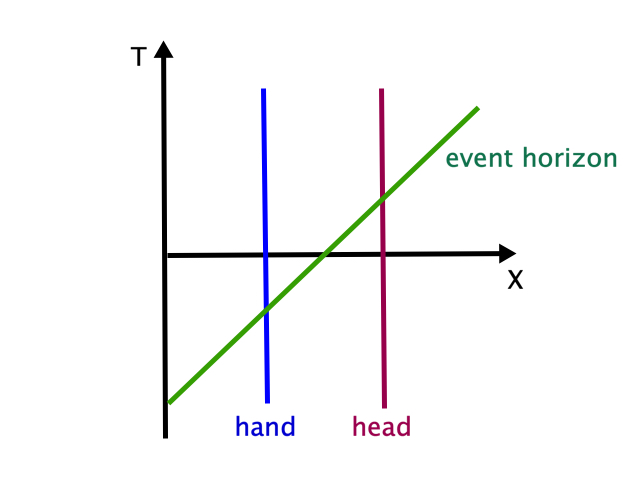

Suppose all parts of my body are at rest in \(X\), \(T\) coordinates. Let’s create a spacetime diagram like the one above to resolve the problem of whether I can feel my hand. The diagram should have \(X\) and \(T\) axes. First, we must work out what the horizon looks like in these coordinates. From the above, we find that \(r=r_s\) where \((3/2)(X-T) = r_s\). On the \(X\)-\(T\) plot, this is a diagonal line, i.e. a path moving outward at the speed of light, i.e. a null path, i.e. an outgoing light cone:

We see that it’s the exact same thing as the light cone case. Assuming my body parts aren’t moving relativistically with respect to each other–if they are, I’m in trouble–my hand inside the horizon will send signals to my head, and by the time the signal reaches my head, my head will be inside the horizon. I can see and feel my hand at all times, oblivious to having crossed an event horizon, but at no point did information travel from the inside of the black hole to the outside!

Now suppose all parts of my body are moving at the same speed, but one different from the frame corresponding to the \(X\), \(T\) coordinates. Say instead that my body parts are at rest in a frame with coordinates \(X’\) and \(T’\). Let’s plot what happens in these coordinates. Naturally, since it’s my rest frame, my body parts will be vertical lines. How about the event horizon? Luckily, since spacetime looks flat/Minkowski in this local region we’ve zoomed into, this is just a matter of a Lorentz transformation. When you do a Lorentz boost, an outgoing null path transforms to…an outgoing null path. This was Einstein’s big point, that the speed of light is the same in all frames. So, the event horizon is still a 45 degree line. In other words, the picture above doesn’t change.

We have resolved the paradox. Hopefully, we’ve done more. We’ve realized that the event horizon is a null surface, like the path of an outgoing isotropic pulse of light. There is no possible observer on the horizon, no frame co-moving with it, no proper time advancing along it. And yet, unlike regular outgoing null surfaces, its area is not growing but holding constant.